Researchers at the universities of Nottingham and Bristol studied behavioural and academic data on more than 11,000 children in Children of the 90s (ALSPAC) at the University of Bristol.

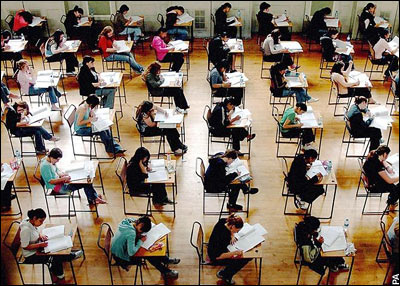

Parents and teachers completed detailed questionnaires when the children were seven years old to assess a variety of different behaviours including inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity and oppositional/defiant problems. This information was compared with the children’s GCSE results at age 16.

After taking into account factors such as IQ, parental education and social class, the researchers found that for every one-point increase in inattention symptoms at age seven, across the whole sample, there was a two to three point reduction in GCSE scores and a six to seven per cent increased likelihood of not achieving a minimum level of five ‘good’ GCSE grades (A* to C) at age 16. This relationship was linear — each one-point increase in inattention symptoms increased the risk of worse academic outcomes across the full range of inattention scores in the sample.

When the researchers took inattention into account, the study also found that, in boys, oppositional/defiant behaviours at age seven pose an independent risk to academic achievement.

These findings have a range of implications for parents, teachers and clinicians.

The research was led by Professor Kapil Sayal, Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham. He said:

Teachers and parents should be aware of the long-term academic impact of behaviours such as inattention and distractibility. The impact applies across the whole spectrum of scores at the population level and is not just confined to those scoring above a cut-off or at the extreme end. Prevention and intervention strategies are key and, in the teenage years, could include teaching students time-management and organisational skills, minimising distractions and helping them to prioritise their work and revision.