Cherry Lewis talked to Professor David Wraith, founder and Chief Scientific Officer, about the vaccine and his struggle to get funding for clinical trials.

David: About ten years ago, Geoff Watts from the BBC came to talk to me about autoimmunity for his Medicine Now programme that went out on Radio 4. One of the things we discussed was a new discovery we’d made that was a way of developing vaccines for treating autoimmune diseases and allergies, so-called therapeutic vaccines. They are based on the concept that has been well known for almost a century, namely allergic desensitisation, where people are given injections of the allergen that causes the reaction.

Cherry: Is that the same principle as a vaccine for smallpox?

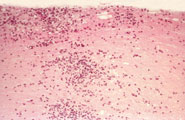

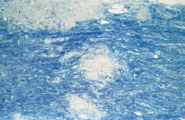

David: Not really. With the smallpox vaccine, you’re giving an attenuated form of the infectious agent which boosts the immune system without actually causing the disease. What we’re talking about here are disorders of the immune system which respond to innocuous things such as house dust and pollen that cause an allergy, or proteins in your body that cause autoimmune diseases. In multiple sclerosis, for example, which is an autoimmune disease, the immune system attacks the myelin sheath around nerve cells – the insulating layer that allows the cells to conduct electrical signals. This causes the nerves to function poorly or die and the symptoms of MS to appear. In these ‘hypersensitivity’ diseases, the immune system is over-responding. We have developed vaccines that can control the immune response, based on the antigens to which the immune system is responding.

Cherry: So how do you activate this desensitisation?

David: There is a set of cells in the body called T-lymphocytes (T cells). Now we know that T cells respond to very small fragments (peptides) of whatever is causing the allergy or the autoimmune disease. We have developed a method of identifying and administering certain peptides so that instead of causing damage, they actually suppress the immune reaction.

Cherry: How very exciting. What happened next?

David: Well, I was talking to Geoff Watts about things and explaining how the biggest challenge we now faced was taking this to the next step, but that it was proving difficult to find funding. Although we have some very large and highly successful venture capital companies in the UK, none of them are funding medical development at an early stage.

Cherry: What’s the reason for that? Is it too high risk?

David: And it’s too long term. But what happened to us was very fortunate. An ‘angel’ investor heard about the programme and offered to help us. He gave us the money to develop our approach to the point where we could take it into clinical trials.

Cherry: That’s a powerful argument in favour of talking to the media.

David: Yes, we had a really great discussion and Geoff got very excited about what we had discovered. I’m sure his enthusiasm helped convey the significance of this work. So the business angel provided enough funds for us to develop the vaccine and do what is called ‘tox testing’ to prove it’s safe. You have to prove that the vaccine is not toxic in animals by giving them doses 500 times higher than you would give humans. When this proved successful we were ready to take it to clinical trials, but then we faced another funding hurdle.

For more than two years we discussed funding with the DTI but that eventually fell through for various reasons. I found the whole business incredibly frustrating. Eventually we were awarded a University Translation Award by the Wellcome Trust and that provided close on £1 million for the first clinical trial in humans. This was set up in 2007 under Professor Neil Scolding in the Department of Neurology at Frenchay Hospital here in Bristol. It was what we call a Phase I safety study.

The aim is to prove that the vaccine can be given safely to humans and there are no adverse effects. Six MS patients at quite an advanced stage of the disease were given our vaccine, memorably called ATX-MS-1467. At the end of the trial, no safety issues had been identified and one patient even showed remarkable improve-ment in her eyesight. I think it’s fair to say that the trial was highly successful.

Cherry: So where are things now?

David: We are now ready to develop the vaccine further and take it to full clinical trials, but we’ve had to raise a lot more money. Dr Keith Martin, who’s the CEO of Apitope, and I have spent the last two years going through endless rounds of talking to funding agencies, venture capital companies, etc, trying to raise the funds, but sadly we haven’t been able to raise any funds in the UK. We had various European investors – from Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, France – all willing to join a syndicate to fund our next development. But in order for us to stay in this country, they needed an investor in the UK to take the lead.

Cherry: And you couldn’t find one?

David: We couldn’t find one. There isn’t a biomedical venture capital company in the UK who doesn’t know about us, who hasn’t looked at our business plan. Finally we were introduced to a group of Belgium- and Luxembourg-based investors who were very interested and we have just signed a deal with them worth 10 million euros (£7.7 million). Apitope will now move to Belgium, locating its head office in Diepenbeek, and be called Apitope International NV. The current UK-based Apitope will stay in the UK and become a wholly owned subsidiary of the Belgian company. Among the funders is the University of Hasselt, which will provide support in exchange for an equity stake and will join forces with Apitope by providing its own research on diagnostics.

Cherry: How do you feel about that?

David: Our decision to move out of the UK highlights the difficulties UK biotech companies have in raising support, even before the recent financial crisis, especially when it comes to bridging the gap between academic-funded research and advanced clinical studies, where the outcomes are a safer bet. Nevertheless, we have now got the funding so the trials will go ahead and ultimately this will lead to safer and more effective treatments for people with MS.

Since writing this article, Apitope International NV has signed a significant licensing agreement to further develop their vaccine.