Health system interventions can improve domestic violence support but context matters

Violence against women is a significant human rights violation, deeply rooted in gender inequalities, affecting nearly one in three women worldwide, with even higher rates in low- and middle-income countries. Health systems play a critical role in addressing immediate health needs and supporting women’s pathways to safety and healing.

Domestic violence, the most prevalent form of violence against women, includes various types of abuse perpetrated primarily by intimate partners and less frequently other family members. Interventions in low- and middle-income countries are at times adaptations of those developed in high-income countries, yet translating these models into diverse contexts with multiple constraints can be challenging.

HERA - Healthcare Responding to Violence and Abuse aimed to strengthen the health system response to domestic violence against women, as well as considering adaptation strategies and implementation challenges across Brazil, Nepal, the occupied Palestinian Territories (oPT) and Sri Lanka.

HERA intervention components:

i) Training and support for healthcare workers to recognise and respond to domestic violence

Training focused on enhancing understanding of womens’ experiences of dealing with violence and building skills for empathy, asking in a non-judgemental manner and providing first-line support. Also, reflecting on social norms that heighten vulnerability to violence, and structural barriers that limit agency and access to support.

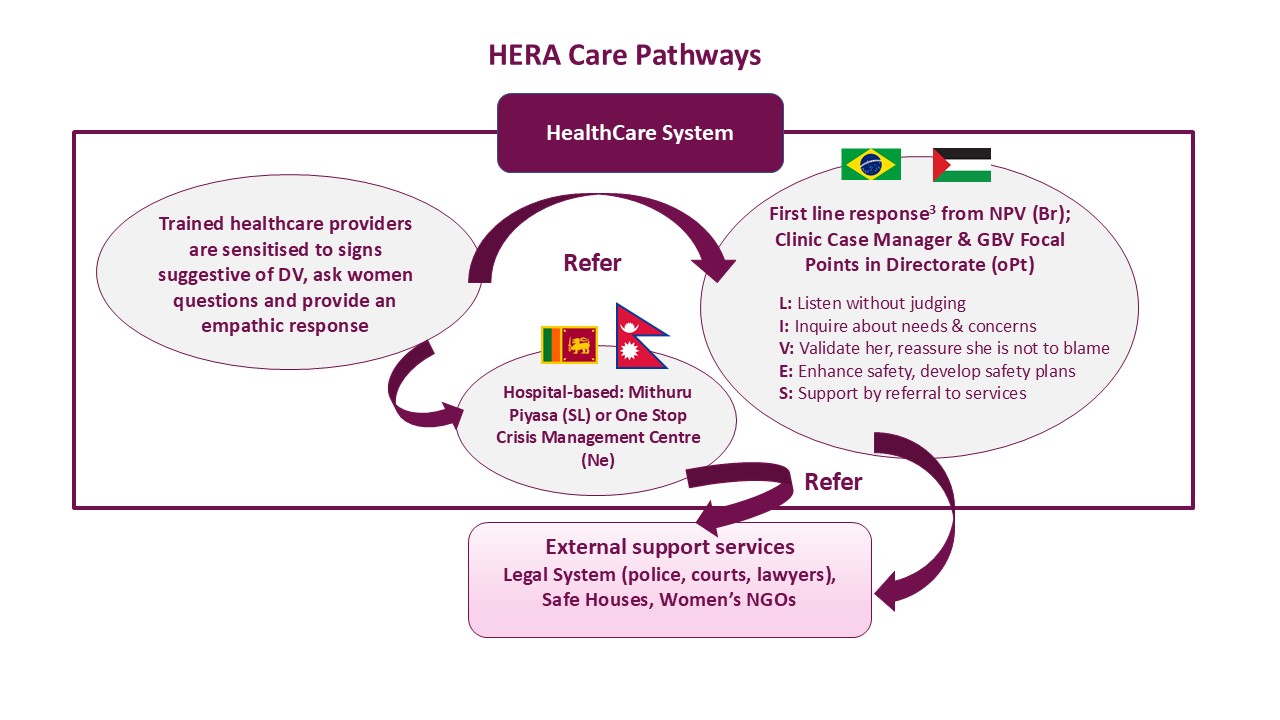

ii) Establishing a care pathway for affected women within and beyond the health system

iii) Improving recording practices

The study took place in health services serving socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, focusing on sexual and reproductive health care.

Policy and practice recommendations

Training and support for healthcare workers

- Incorporate a robust women-centred perspective in training programs, grounded in an understanding of gender inequality, along with dedicated opportunities for reflective practice and specific scenarios.

- Develop targeted interventions for managers to effectively drive organisational change, such as incorporating communities of practice and mentoring approaches.

A care pathway for women

- Strengthen health system linkages with local leaders, women’s organisations, and NGO-led services to boost community awareness and support for domestic violence interventions, and ensure culturally relevant approaches.

- Expand referral options for women at various stages of readiness to seek help, including both formal organisations and informal support sources like community-based groups.

Recording practices

- Maintain a simple, unified record system for documenting domestic violence, ensuring strict confidentiality to reduce under-reporting.

- Establish targets and performance indicators for domestic violence responses in healthcare systems to enhance the integration of interventions into existing accountability frameworks.

Key findings

- HERA increased the identification of women experiencing domestic violence across three countries, achieving increases of 69% in Sri Lanka, 78% in Brazil and 100% in Nepal, while the occupied Palestinian Territories experienced a 24% decrease, partly due to escalating violence in the Israeli occupation.

- Healthcare worker confidence and motivation to address domestic violence improved, with reported increases in readiness to identify, inquire about and respond to domestic violence by documenting cases, making referrals, and offering ongoing support. In Nepal, there was a slight decrease in healthcare worker confidence to offer ongoing support due to the healthcare clinics becoming Covid isolation wards.

A women-centred perspective

- Care for women went beyond simply identifying, documenting, and referring cases of domestic violence. It embraced a holistic approach, focusing on empathy, understanding social contexts, shared decision-making, and respecting women’s autonomy.

- Women reported that supportive, compassionate interactions were crucial in creating person-centred and empowering experiences during disclosure.

- Not all women wanted to pursue the referrals offered; many preferred ongoing supports from the healthcare workers they initially disclosed to.

“The nurse tried to calm me down. She looked at me as a human being…She said, ‘you cannot suffer all of this alone, you really need to share this’. I saw changes (after talking with the nurse). I could think, someone knows that I go through this. I have to organise myself, my ideas…my life to get out of this. I felt a little more secure to have gone there and talked to this professional.” Woman, Brazil

Training and support for healthcare workers

- The training emphasised the need for understanding how unequal power dynamics between men and women drive domestic violence, and how to avoid replicating these in the health system, driving the need for women-centred care.

- Implementing a women-centred response required creating spaces for healthcare workers to reflect collectively on their practices and problem solve.

- In Brazil, supervision sessions integrated into existing multidisciplinary clinical meetings of the NPV (Violence Prevention Nucleus) helped sustain ongoing reflection and discussions on domestic violence cases, supporting implementation of HERA.

- In the other countries, these structures were lacking, and collective reflection relied on periodic refresher training, often delivered by external facilitators, indicating a lack of health system support to embed continuous learning and supervision.

- Some healthcare workers, particularly in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and occupied Palestinian Territories, struggled to adopt new approaches, as their views on domestic violence and gender norms were shaped by deeply ingrained cultural values about family roles, honour, and traditional gender hierarchies.

“In reality, whatever we do, it is only when we do things practically [working with the patient], that we get to understand the feelings of a patient, the gravity of the problems...the role play includes how they feel and many other things ... We have to be a lot more empathetic and identify the feelings of the patient. That ‘silence’ is very valuable here.” Nurse, Sri Lanka

Interventions for managers

- Effective leadership was crucial for driving organisational change in the clinics. Leaders played a key role in shaping how staff understood their roles and encouraged shifts in beliefs and practices, guiding appropriate actions in different situations.

- Leadership support varied across and within countries, often reflecting the motivations and values of managers at different levels. Examples include the creation of clinic case managers in occupied Palestian Territories, extending training from private to public healthcare facilities in Nepal, making space within clinical meetings for case discussion in Brazil, and involving the Family Health Bureau of the Ministry of Health in Sri Lanka in the development and delivery of training.

- Provider Intervention Measure (PIM) surveys revealed that healthcare workers in all countries felt more supported by their organisations in handling domestic violence cases after HERA, except in occupied Palestinian Territories, where they felt less protected. This decline in perceived protection was linked to a significant escalation in violence resulting from the Israeli occupation that coincided with the study period.

Recording practices

- The presence of multiple clinical record systems for different purposes led to inconsistent and poor domestic violence documentation practices. Healthcare workers often navigated these complexities differently, and many were hesitant to document violence due to fears of community exposure or retaliation from the aggressor. In some cases, documentation was negotiated with women, leading to incidents of violence going unrecorded.

“Ninety percent of these women refuse to report the cases…One woman totally refused to have her case documented. You can’t force anyone. There is no imposition, but this woman still comes to see me. She just does not want to be documented.“ Gender-Based Violence Focal Point, occupied Palestinian Territories

Context matters

The adaptation and implementation of HERA in the four countries was shaped by their distinct socio-cultural, political and economic contexts.

Social Violence - Healthcare workers in occupied Palestinian Territories and Brazil reported that violence relating to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and drug cartels respectively, placed them in environments marked by social violence, making them more susceptible to aggression than their counterparts in Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Gender Norms - Gender norms and variations in laws regarding violence against women influenced how healthcare workers perceived and responded to women, also affecting women’s ability and willingness to seek support.

Covid-19 - The Covid-19 pandemic further complicated these efforts, challenging all health care systems and requiring healthcare workers to prioritise their response to the pandemic over implementation of HERA.

“Violence against women was less of a priority for health care. Fever clinics decreased outpatient functioning at the Outreach Centres, thereby decreasing the possibility of identifying violence against women. (There was) transfer of staff, as an isolation ward was established at the outreach centres by the government for infected healthcare workers.” Researcher Field Notes, Nepal

Implications for future research

- Account for the interaction between context and intervention goals when developing, implementing, and evaluating health system responses to violence against women.

- Investigate what defines positive outcomes for women at various stages of readiness to seek help and awareness of their situations, considering their diverse contexts, to develop tailored interventions.

- Determine which targeted health system interventions - such as leadership development, peer support, and communities of practice - are most effective in sustaining organisational change.

Details of the research

The study took place in health services serving socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, focusing on sexual and reproductive health care. This included primary healthcare facilities in Brazil, Nepal, and the occupied Palestinian Territories, as well as in district general hospitals in Sri Lanka.

Healthcare workers followed the WHO Clinical Handbook to deliver a women-centred response.

HERA was shaped by a formative research phase and stakeholder workshops, tailoring the approach to each country.

From 2019 to 2022, each country conducted a mixed-method evaluation to assess both processes and outcomes. Data collection included the Provider Intervention Measure (PIM) to quantify changes in healthcare workers attitudes and behaviours, as well as clinic records to assess the identification and documentation of domestic violence.

Qualitative data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with healthcare workers, managers and women survivors, along with field notes and focus groups with key stakeholders conducted across all four countries.

Further information

- Sardinha et al. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical, or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018, Lancet. 399(10327): 803-13.

- HERA (Healthcare Responding to Violence and Abuse) study website

- World Health Organisation (2014). Healthcare for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. A clinical handbook

- Colombini & Shrestha et al. (2024). Comparing health systems readiness for integrating domestic violence services in Brazil, occupied Palestinian Territories, Nepal and Sri Lanka, Health Policy & Planning. 39: 552–63

- Bacchus & Pereira et al. (2024) A multi-country mixed method evaluation of HERA (Healthcare Responding to Violence and Abuse) intervention: a comparative analysis. Social Science & Medicine Health Systems (forthcoming)

Acknowledgements

HERA is a collaboration involving University of Bristol, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University of São Paulo, Kathmandu University, South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Centre at University of Peradeniya, and An-Najah National University.

Authors

Loraine J Bacchus, Manuela Colombini (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine), Stephanie Pereira, Ana Flavia d’Oliveira, Lilia Blima Schraiber (University of São Paulo), Poonam Rishal, Kunta Pun (Kathmandu University), Thilini Rajapakse (University of Peradeniya), Amira Shaheen, Abdulsalam Alkaiyat (An-Najah National University), Claudia García-Moreno (World Health Organization), Gene Feder (University of Bristol), HERA team

Policy Briefing 163:

Nov 2024

Health system interventions can improve domestic violence support (HERA) 2024 (PDF, 1,057kB)

Contact the researchers

Prof Loraine J Bacchus, Professor of Global Public Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Loraine.Bacchus@lshtm.ac.uk

Prof Gene Feder, Professor of Primary Care, University of Bristol Gene.Feder@bristol.ac.uk

![]()