History

Introduction

St. James' Church behind the White Hart Inn

Very few prospective Bristol dental students will realise the history which lies all around them and beneath their feet as they work and relax at the Dental School. The most obvious historic feature which might have impinged on some as they made their way back to the Bus Station was the church of St James built as part of the Benedictine Priory by Robert Earl of Gloucester in 1138, and in this photograph almost lost behind the White Hart - at 300 years old a relative newcomer! The church is now mostly hidden behind a new hostel for the homeless.

The Romano-British Period

The site on Upper Maudlin Street where the 1985 Dental School extension now stands marks the site of the earliest known Romano- British settlement within the city. Much of this site, which was excavated in 1973, had been destroyed by the building of the Moravian Church which was in its turn demolished to make way for the Wellcome Building and the 1985 extension. So as staff and students drink at the Hathorn Bar on Friday nights they are doing so on a site of known habitation in Bristol for 1800 years.

Greyfriars

Plan of St Augustine's Abbey

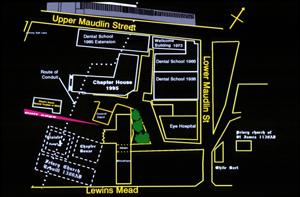

The present Dental and Eye Hospitals also lie on the site of what was another major religious establishment in Bristol: that of the Friars Minor or Greyfriars. These were not Benedictines as at St James, but Franciscans who had first arrived in Bristol in 1220. Sometime in 1250 a site for them was found here possibly on land given by the Benedictine Prior of St James. Their eventual precinct, as reported by William Worcestre writing in 1480 was bounded by Lower Maudlin St on the East, Upper Maudlin St on the north, Johnny Ball Lane on the west and Lewin's Mead to the South.

Like all other religious houses this continued up until the time of the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538. Bristol had many such houses from the large order of Blackfriars who founded St Augustine's abbey which later became Bristol's cathedral to the tiny St Mary Magdalene's priory at the foot of St Michael's Hill from which Maudlin Street gets its name. All of these establishments stood outside the city which at that time was walled and protected a marshy area at the junction of the rivers Avon and Frome.

The effect of the River Frome

Chapter House

In order to understand the Greyfriar's site it is necessary to have some idea of the local geography at the time. In 1250 Bristol was a small town with a growing port on the banks of the tidal Avon. In 1239 work had begun to realign the River Frome in order to improve the harbour. It was this huge engineering project completed in 1247 which enabled Bristol to become a great port and at the same time created the site for the future Greyfriars priory. If you walk towards Lewin's Mead from the new Chapter House you will come to wall from which you can look down over a cliff which marked the northern extremity of the sweep of a very marshy River Frome. This river used to curve round the north of the walled town before heading south to enter the Avon near Bristol Bridge.

With the encouragement of Henry III the Frome was realigned to its present course. It now flows unseen into the floating harbour by Neptune's Statue but you walk across the Frome everytime you visit Marks and Spencers for it still runs on the same course under Rupert Street. From 1255 until 1938 the Frome used to provide moorings running the length of the Centre in what was known as St Augustine's Trench with St Augustine's parade on one side (the Hippodrome side) and Colston Avenue/Broad Quay on the other.

It was the new alignment of the Frome which allowed the previously marshy site for Greyfriars to be drained (and brought into existence the meadow from which Lewin's Mead takes its name). There is also evidence that much of the spoil from the excavation of the new river channel was deposited on what was to become the Greyfriars site. The 1973 excavations by the City Museum found a 1 metre band of clay and red rock added above the alluvial deposits of the old river.

The friary was expanded and largely rebuilt in 1386. The rebuilt 50 metre church was sited beneath the present Greyfriars building. There was a cloister to the north of the church (about in the open area between the Greyfriars and Whitefriars office blocks) and a chapter house to the east of the cloister behind the present Council Depot; about 30 yards due south of where the new Dental School Chapter House stands. Excavations have shown that the buildings were constructed of local red rock bonded with a red sandy mortar. They must have looked very similar to the walls of the present St James' church. Some fine stained glass was recovered from the Greyfriars chapter house which is now in the City Museum.

The end of the Greyfriars

In 1540, following the dissolution of the monasteries 2 years before, Jeremy Green obtained a lease from King Henry VIII on most of the Greyfriars estate. A year later the site was sold to the Mayor and Corporation. The description of the letters patent dated May 6th 1541 give a good idea of how extensive the friary was at its dissolution.

"All the house and site of the late house of the Minor Bretheren, commonly called Greyfriars, within one said town of Bristol now dissolved and all our houses, buildings, barns, dovecotes, gardens, orchards, burial places, waters, pools, vivaries (a place artificially prepared for the keeping of animals or fish), land and soil as well within and near to and about the site of seven ambits in circumference of the said late house of the Minor Bretheren..."

The Chapter House

The Chapter House

So what was a Chapter House? In this context a "chapter" refers to a group of canons, or members of other religious orders. The Chapter House was usually a separate round or octagonal chamber where the fraternity met for both secular and spiritual purposes in connection with the running of their order. You will find chapter houses attached to most cathedrals originating from the times when they served the needs of pre-reformation religious orders.

The term chapter house is still used in the United States to denote the place where a university college fraternity (or sorority - the female equivalent) meets. This is not surprising since the first universities evolved from religious establishments as their quadrangles, refectories and cloisters indicate. It follows that university lecture theatres and great halls have their origins in the chapter houses of monasteries and friaries rather than the halls and salons of great town and country houses.

It might be thought that Bristol's own University, founded as it was as recently as 1913, was too late to have any connection with a medieval religious establishment. But it should not be forgotten that John Percival who took the lead in calling for a University for Bristol and in 1901 became President of the newly founded University College which preceded it, was a former Bristol Canon who had become Bishop of Hereford in 1895.

The Abbot's House

The Abbot's House

During the demolition of an old building in 1989 to make way for the new Special Trustees offices being built on the newly acquired Trust/University site, a medieval roof structure was discovered indicating that the building had been part of Greyfriars building.

The replica which was subsequently built echos this origin. The small oval window at the top of its Eastern frontage comes from the original structure.

And finally . . .

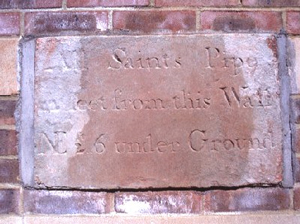

"All Saints Pipe, feet from this Wall 2ft 6 under Ground"

One final link with the past. Some of you may have noticed the old stone which has now been reset in the wall of the Chapter House facing the Abbots House just before the steps which lead up to our "cloister".

This late 18th century stone marks the line of the water calvert of conduit (pipe) which served the friary and carried water down to the pump in the cloister. The spring had been granted to the Greyfriars at the end of the thirteenth century and when the order was dissolved in 1538 the water supply was taken over by All Saints Parish to serve the local people. The same 1973 excavations revealed a more modern structure which ran within the earlier medieval conduit.

There are a number of such "pipes" in Bristol most of which have branches. Perhaps the most famous is St John's Conduit built to supply the Carmelite friary built on the site of the present Colston Hall from a spring on Brandon Hill. This still exists and has a branch pipe which still supplies the water for the public fountain set in the church wall of St John's on Nelson Street.

Chris Stephens

Further reading

- Buchanan A, Cossins N. Industrial archaeology of the Bristol Regions. David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1969.

- Ponsford MW. Excavations at Greyfriars Bristol. City of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, 1975

- Little B. The story of Bristol. Redcliffe Press, Bristol, 1991.

- Watson S. Secret underground Bristol. Bristol Junior Chamber, Bristol, 1991.

- Winterbottom D. John Percival - the great educator. The Historical Association, Bristol.