Annual Report

1998-99

![]()

The Henri Martin

scandal

The play, banned by some local authorities, had received a tumultuous

welcome in the early 1950s. Audiences had packed cinemas, gathered in

barns, applauded and wept at an open-air performance at the entrance to

the courtroom in which its hero was being tried. The play was probably

seen by 200,000 spectators all over France. Jean-Paul Sartre referred

to it as the only example of popular theatre known to him. Yet, until

1998 this play was virtually lost: unpublished and unknown. It is Drame

à Toulon—Henri Martin by Claude Martin and Henri Delmas.

Ted Freeman was able to track down Henri Martin himself and the surviving author, Henri Delmas, both living in Paris. He has edited the text, written an introduction and published the play for the first time. In this he was helped by a University Research Fellowship which gave him a year free from his duties as Senior Lecturer in French in order to pursue his research.

| A portrait of Henri Martin by Picasso |

Henri Martin’s name was familiar in France in the early 1950s—daubed on bridges and buildings—as the victim of a miscarriage of justice. Having played a part in the Resistance, he served in the French navy in the Vietnam war and conducted a leaflet campaign against the savagery of this war. He was court-martialled on doubtful grounds and sentenced to five years in jail. This excited a passionate defence campaign in France, to which the play contributed.

Material on Drame à Toulon—Henri

Martin also forms a chapter of Ted Freeman’s major publication, Theatres

of war: French committed theatre from the Second World War to the Cold

War. This is the first full-length study to be devoted to the distinctive

genre of ‘Committed’ theatre that was performed in France from 1944 to

the mid-1950s. The book covers all the best-known dramatists in the genre,

as well as many plays which, although they enjoyed successful productions

in Paris at the time, have never before been studied in accounts of modern

French theatre history.

Drame à Toulon

- Henri Martin edited, with introduction, by Ted Freeman, University

of Exeter Press, 1998. Theatres of War: French Committed Theatre from

the Second World War to the Cold War by Ted Freeman, University of

Exeter Press, 1998.

Detecting tainted

pork

Farmers are faced with a dilemma: the pork which comes from boars which

have not been castrated is lean and tasty, but occasionally it is affected

by ‘boar taint’, giving it a flavour which has been described as ‘sweaty’

or ‘dirty’, reminiscent of ammonia, parsnip, silage or mothballs. The

meat industry needs a quick and reliable method of detecting which carcasses

are affected.

Two chemicals found in pork are associated with boar taint: androstenone and skatole. Geoff Nute, Research Fellow in Food Animal Science, and colleagues in Ghana and Bristol, have carried out experiments with a panel of expert testers who sniffed samples of the two chemicals in varying concentrations in vegetable fat. However, although they detected the presence of androstenone or skatole, there was a wide variation between individual assessors and what they found unpleasant, and no clear correlation between the concentration of the chemicals and the intensity of the smell. Geoff and his colleagues concluded that to test for boar taint it was necessary to find some other objective test.

The answer lay in an ‘electronic nose’. The e-nose (Neotronics Olfactory Sensing Equipment) had 12 conducting sensors and simulated the methodology often employed by analytical chemists. The findings of the e-nose correlated closely with the human testers and the pork could be classified in three categories: normal, doubtful and abnormal. Most importantly, the e-nose and the testing panel agreed on all the samples in the ‘abnormal’ category. Thus the research group has found that, despite the cost of the equipment, an e-nose can substitute for a trained sensory panel which is a time-consuming and expensive alternative.

A new nose

Jim Baldwin, Professor of Artificial Intelligence, and Steve McCoy, Research

Assistant in Engineering Mathematics, are working on a new

e-nose. Electronic noses typically cost upwards of £15,000 and are still

in an early stage of development. Most systems operate by measuring changes

in sensor resistance when exposed to chemicals. The research group in

Engineering Mathematics, partners in a European ESPRIT project, are using

a novel software approach.

The e-nose learns typical shapes for sensor responses in the form of fuzzy rules, for example, according to sensor 1, the substance is likely to be x if the signal initially increases sharply on exposure, then decreases slowly back to its rest value. These rules are generated automatically by the Fril data browser from a few examples, typically less than five. The browser automatically creates further rules to fuse the classifications from each sensor into an overall decision. It can also use this information to determine which sensors are best for a particular classification task.

The researchers have tested the system on single substances and binary mixtures at various concentrations, and over 90% of the results have been classified correctly. They are now moving on to live test data, based on the acceptability of packaging materials for food.

The Hearing Group

Researchers in the Department of Physiology are building an ear in a

test-tube. Many people will remember the photographs of the mouse with

an ear on its back. But the part of the ear that you can see is only involved

in helping us to localise sounds. The really important parts of the ear

that enable us to hear and balance are surprisingly small, protected by

the hard bones of the skull and extremely difficult to study experimentally.

The biggest problem is that the sensory cells that detect sound, the hair

cells, are produced before birth and are not replaced in subsequent life.

Thus most forms of deafness are irreversible.

|

A sensory hari cell isolated from the inner ear. From top to bottom is measures about 35µm.m |

To get into the inner ear and discover more about the mechanisms of development, Matthew Holley, Senior Research Fellow, and Corné Kros, Lecturer in Physiology, have recently obtained grants of over £1 million from The Wellcome Trust, The Colt Foundation and Pfizer Central Research. The aim is to recreate developmental processes in cell culture in order to identify some of the key genes and physiological events that might be used as a basis for therapeutic regeneration of hair cells. Helen Kennedy, Research Career Development Fellow, and Nigel Cooper, Royal Society University Research Fellow, provide further expertise in the physiology of single cells and of the whole inner ear.

The scale of the experimental challenge is reflected by the fact that the sensory cells can detect sound vibrations of less than one-millionth of a millimetre. Fortunately, the research group provides the expertise to integrate the latest techniques in molecular biology, cell biology and systems physiology, an essential combination to meet the research opportunities of the new Millennium.

Plague rats

Between AD541 and 547, during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian,

a massive pandemic of bubonic plague spread across the Mediterranean and

into Northern Europe. It decimated the cities of the East and of North

Africa; in Constantinople alone the plague claimed up to 16,000 victims

a day, and officials counted 260,000 bodies before giving up, or succumbing

themselves. The classical writers realised that the plague spread from

Africa, but exactly where it came from has never been established. It

was most likely carried via infected fleas on the ships’ rats on trading

vessels.

Mark Horton, Reader in Archaeology, with colleagues on Zanzibar, has been excavating at Unguja Ukuu, one of the main ports of the island. It has been discovered that during the Justinian period there was a renewed interest in carved ivory and a massive demand for large pieces of ivory, which could only be supplied from sub-equatorial East African elephant herds. The researchers at Unguja Ukuu have discovered typical sixth-century pottery from the Mediterranean, pointing to trading links between Zanzibar and the Justinian court. At the same time bones of the black rat, Rattus rattus, were identified in the excavations. Taking the archaeological evidence and the fact that even today there is a reservoir of plague-carrying fleas on Zanzibar, it is very likely that the holds of the ships which bore precious cargoes of ivory to Constantinople also harboured black rats and plague-ridden fleas. Thus the Great Justinian Plague was spread, not only to Byzantium but far beyond and even to South West Britain and Ireland.

Ancient greenhouse

effect

The greenhouse effect is nothing new, according to researchers in the

Department of Earth Sciences. Paul Pearson and Martin Palmer have been

using a new technique to reconstruct ancient levels of carbon dioxide

in the atmosphere. They have found that the amount in the early Eocene

period (50 million years ago) was much higher than the present day. The

world was also a lot warmer at that time, with tropical forests and mangrove

swamps blanketing southern England. The mean annual temperature in southern

England was about 25oC, compared to 10oC today.

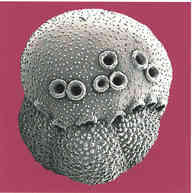

|

A fossil foraminifera shell, half a millimetre across |

Obviously it is not possible to sample ancient atmospheric gases. The technique that Pearson and Palmer have developed relies on the fact that high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would have made the surface ocean more acidic than it is now. Living in that ocean were tiny planktonic organisms, called foraminifera, that secrete a minute mineralised shell. These shells survive as fossils, and retain valuable information on the acidity levels of ancient seawater.

The key chemical variable is the isotopic ratio of the element boron. Shells from a more acidic ocean would be expected to have less of the heavy isotope, 11B, than modern ones. That is exactly what Pearson and Palmer have discovered. Their results imply levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide more than three times the modern concentration. This might well have been sufficient to trap more of the sun’s heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, and so cause the uniformly high global temperatures that are inferred for the Eocene period.

The result is of little comfort for us, as we enter a new and uncertain century. The concentration of carbon dioxide is currently rising so fast, due mainly to fossil fuel burning, that we may see levels similar to that inferred for the Eocene by 2100. Pearson and Palmer stress that this does not necessarily mean we will recreate ‘Eocene’-type conditions. There are still too many unknowns involved in climate prediction. But the sweltering ice-free world of the Eocene does warn us of what might happen if a runaway greenhouse effect sets in.

Measuring ozone

Ozone plays a pivotal role in the Earth’s atmosphere, yet until now it

has been impossible to measure concentrations of ozone in the mid- to

upper-atmosphere with any degree of accuracy. Large discrepancies exist

between the ozone concentrations calculated from computer models of the

atmosphere and the observed ozone concentrations inferred from satellite,

rocket, and ground-based observations for altitudes above about 50 km

(ie, above the ozone layer, which is at an altitude of 25-30 km).

Ozone absorbs strongly in the ultraviolet, and the energy of the absorbed solar radiation causes an oxygen-oxygen bond to break, forming O atoms and electronically excited O2. The latter can decay back to the lowest energy electronic state by emitting a near infra-red photon. By measuring the rate of emission of photons it is possible to determine ozone concentrations. However, emission rates are very low and therefore difficult to measure using traditional spectrometers. The key parameter describing the rate of emission is called the Einstein A-coefficient, and previous laboratory measurements of this have been uncertain to within a factor of 2.

Now Stuart Newman, a postgraduate student in the School of Chemistry, aided by Ian Lane, a postdoctoral researcher in Andrew Orr-Ewing’s research group, has evolved a new method. They have determined the Einstein A-coefficient by measuring an absorption spectrum of O2 at the appropriate wavelengths using two very sensitive techniques. The first instrument is a high-resolution Fourier transform spectrometer (FTS) and absorption cell located at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire. The second instrument, in the School of Chemistry, is a laser-based spectrometer that employs the recently developed technique of cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS). The CRDS apparatus, just 1.5 m long, traps a laser pulse between two ultra-high reflectivity mirrors. This results in the pulse travelling up to about 10 km through the O2 sample. A series of careful CRDS and FTS spectral measurements of the strength of the O2 absorption for known pressures of O2 have permitted independent determinations of the Einstein A-coefficient that agree to within 3% of each other. The new, precise value will allow better comparison of atmospheric measurements with the computer models of the chemistry and thermal structure of the middle atmosphere. The project was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council.

Green solvents

The two most abundant and inexpensive solvents on Earth are water and

carbon dioxide (CO2) which can be liquified under pressure. Mixtures of

these two fluids have a vast potential as ‘green’ solvents to replace

toxic and hazardous petrochemical solvents which are currently in use.

However, CO2 is a poor solvent because its molecules have only weak interactions

with most other substances, hence it is generally of limited utility.

To overcome this problem a team headed by Julian Eastoe, Reader in Physical Chemistry, is developing novel soap-like molecules, or surfactants. Instead of containing hydrogen, like conventional materials used in washing-up liquid, these specialised molecules bristle with fluorine atoms at one end. This optimises interactions between the surfactant and CO2. At the opposite end of the molecule an ionic group makes it water-soluble. This finely balanced chemical structure makes the surfactants remarkably efficient in a mixture of water and carbon dioxide. These dispersions, known as microemulsions, have excellent stability, which makes them ideal for a wide range of applications, including cleaning fluids for the electronics and aerospace industries.

This research, funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, is multi-disciplinary and multi-centred. The surfactants are synthesised and characterised at Bristol. The stability of water-CO2 mixtures is investigated by a team from the University of East Anglia and finally, the droplet structures are studied by neutron scattering at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory.

Search for a universal

vaccine against meningitis

The bacterium responsible for causing the most serious form of meningitis

and septicaemia, Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus), comes in several

varieties. In the UK mainly two types (Group B and Group C) cause disease.

Recently an effective vaccine has been introduced against Group C strains,

which are responsible for approximately 40% of the cases. However, this

vaccine will not prevent the remaining cases of meningococcal disease

for which the Group B strains are responsible. Therefore, there is still

a need for a broadly effective vaccine. Perhaps by understanding the mechanisms

by which meningococcus causes disease, new universally effective vaccines

can be devised. Research in the laboratory of Mumtaz Virji, Professor

of Molecular Microbiology, is directed to achieve this aim.

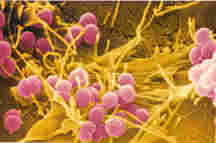

|

Meningococci binding and invading human cells |

Meningococci may be present in the nose and throat cavities of up to 30% of healthy individuals. Only in a small number of individuals, the bacterium enters deeper into the body. When it does this, it spreads very rapidly to cause blood infection and colonise the brain, causing septicaemia and meningitis. It is not clear what makes it possible for this bacterium to pass across the natural cell barrier of the nasopharyngeal cavity in susceptible individuals. It has been suggested that some individuals may become susceptible to infection following certain viral diseases. However, there are other factors that make children and young adults more susceptible than other groups. One of the ways to prevent disease is to preclude meningococci from colonising the human population; this has the advantage of protecting all vulnerable groups against all forms of meningococci.

Mumtaz Virji is investigating the ways of preventing bacterial attachment. ‘To do this’, she says, ‘We need to identify molecules that the different bacteria use to make it possible for them to attach and invade the vulnerable host.’ Her research group has found that meningococcal proteins known as Opa and Opc, that are involved in attachment, target particular molecules on human cells. These human molecules increase in number during inflammation (eg following a viral infection). Consequently, more bacteria may become attached to the host cells. This may result in invasion of the cells and entry into deeper tissues beyond the nose and throat. Part of Mumtaz Virji’s current research is targeted to testing this hypothesis. In further work, she hopes to identify other factors that are involved in the complex relationship of this bacterium with its human host. Such studies will lead to a deeper understanding of the disease and, with this knowledge, to the development of future broadly effective vaccines to protect all vulnerable groups.

A vaccine as a

male contraceptive?

For years scientists had been puzzled: men

whose partners had difficulty in conceiving often had a high rate of free

radicals in their semen. Were these gangs of reactive molecules attacking

the sperm? Now Len Hall, Professor of Molecular Genetics, has discovered

a new enzyme which protects the sperm against attack. Known as GPX5, it

is made exclusively in the reproductive tract and coats the head of each

sperm, forming a protective barrier which the free radicals cannot penetrate.

It is likely that any man unable to produce GPX5 would be infertile, but

this will be the subject of further research.

The discovery of the new enzyme may lead to a form of male contraception. This could be a chemical inhibitor which would be designed to interfere with the activity of GPX5. It would be straightforward to produce and, since GPX5 is only found in the reproductive tract, it would not affect tissue or proteins elsewhere in the body. The drawback is that such a drug would need to be taken often. So Len Hall’s team is looking to the growing field of immuno-contraception, in which contraceptives are administered as vaccines. He says, ‘The idea would be to inject someone with the protein, and the body would produce an immunological response in the form of antibodies. The antibodies would bind to the enzyme and stop it working. Such a vaccine could be administered, say, every six to 18 months. It would be reversible, a person would simply have to wait for the vaccine to wear off.’ Even though male pills have had a mixed history and any such contraceptive is unlikely to come to market for a decade or so, Len Hall hopes that his research will lead to a product. ‘If a cheap, safe contraceptive can be found there will be a huge market.’

Brain imaging and

craving for heroin

Using the state of the art neuroimaging technique of PET (Positron Emission

Tomography), David Nutt, Professor of Psychopharmacology, and colleagues,

have been looking for the areas of the brain that are involved in the

feeling of craving for heroin. PET involves the injection of radioactive

water to generate pictures of brain activity. This water flows where the

blood flows in the body. Because blood flow is increased in parts of the

brain that are active, the researchers can generate pictures of brain

activity and see which parts of the brain are concerned when people are

craving. The research team thus hopes to gain a better understanding of

this process, which is particularly important because it is a common reason

that ex-addicts give for relapse to drug use. One of the areas (the left

anterior cingulate gyrus) found to be involved in craving has also been

implicated by US researchers in craving for cocaine, and it is interesting

because it is also known to be involved in attention and processing of

emotions.

This work is part of an ongoing multi-study programme of research being carried out by the Psychopharmacology Unit in collaboration with the MRC Cyclotron Unit, Imperial College, and drug and alcohol treatment services in Bristol and Weston-super-Mare. The research programme is intended to extend our knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of addiction to heroin, alcohol and other drugs. Other studies currently underway look at craving for alcohol, the brain’s responses to drugs of abuse, and the changes that occur in the brain while opiate users are coming off drugs. The Unit is always looking for control subjects and offers anyone who takes part a picture of their brain in return.

Alcohol consumption

and mortality

Can there be pleasure without pain? There have been numerous studies investigating

the links between alcohol consumption and mortality. George Davey Smith,

Professor of Clinical Epidemiology, with colleagues in the Universities

of Glasgow and Michigan has followed up nearly 6,000 men employed in the

west of Scotland who were screened in the early 1970s. The men, aged 35-64,

had answered questions on their usual weekly alcohol consumption. For

those who died in the following 21 years the researchers studied the cause

of death, looking particularly at coronary heart disease, stroke and alcohol-related

causes.

The results differed from previous studies. There was no clear link between death from coronary heart disease and alcohol consumption once adjustments had been made for socioeconomic and other factors. However, those men who drank more than 35 units a week were twice as likely to die of stroke, and drinkers of more than 15 units a week had significantly higher risks of stroke than non-drinkers. Overall the risk of death from all causes was higher in men drinking 22 or more units a week than among those who drank less. In the survey the category of non-drinkers consisted of lifetime abstainers, occasional drinkers, former drinkers, and possibly (the researchers admit) men not admitting to drinking alcohol. They tended to be older, less likely to be in manual occupations or live in deprived areas, had fewer siblings, were less likely to smoke and more likely to be car users.

This important study has deepened our knowledge of the relationship between alcohol and mortality, but it also points to a further field of study: the effects of binge drinking.

Childhood health

and diet affect adults

Recent research suggests that the important diseases of old age, in particular

cancer and heart disease, may have their origins in early life and childhood.

A research team in the Department of Social Medicine has been following

up a group of around 5,000 men and women who took part in a pre-war survey

of diet and health. The survey, conducted between 1937 and 1939 by a team

led by the eminent nutritionist Sir John Boyd Orr, was the largest survey

that had ever been carried out into the diet and health of Britain’s children.

Study members are now in their late 60s and early 70s and the researchers

have managed to trace over 85% of the original 5,000. To date, 1,000 have

died, and 1,500 of the survivors recently completed a detailed questionnaire

on their current diet and health. This unique study has been used to examine

the long-term associations between childhood diet and adult health.

The research team has recently shown, for the first time in humans, that childhood energy intake influences later cancer risk. They have also found that nutritional status and overweight in childhood is associated with an increased risk of heart disease and cancer.

Screen play: kids

& computers

Despite a multitude of pronouncements on the subject, there has been surprisingly

little research into young people’s experience of computer technology

out of school. Which young people have access to televisions, videos and

computers? What effect do new technologies have on their lives? How do

they learn to use computers, and have computers affected the way they

learn in general?

John Furlong and Rosamund Sutherland, Professors of Education, together with Ruth Furlong at the University of Wales and Keri Facer at Bristol, are investigating these questions. They are drawing on cultural studies and educational research, exploring the child’s interaction with the computer outside school, examining the child’s social context and the way this may shape or be shaped by the technology introduced into the home. The project, entitled Screen play, is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The research team has surveyed 855 children aged 9-10 and 14-15 in eight schools in Wales and South West England and is currently interviewing 16 children in their homes and with friends.

Preliminary findings show that whereas almost 100% of the families own at least one television set, computer ownership decreases quite considerably with income group (upper income 80.4%, middle income 68.1%, lower income 53.9%). On the other hand, the ownership of games consoles increases as income decreases. Analysing personal ownership by gender, the researchers found that whereas more boys (62%) than girls (39%) own a games console, there is almost no difference in terms of personal ownership of PCs: 19% of girls and 22% of boys (interestingly more girls than boys have a personal telephone). Children who do not have a PC in their homes are significantly less likely to use a computer at a friend’s house (40% as against 64%). The children used computers mainly for games (75%), writing (65%) and drawing (59%). Despite comments such as, ‘I really hate computers because they go wrong so often and are really complicated’, a more typical response was,‘I love them. They’re the best thing since sliced bread.’ The ongoing interviews with young people in their homes and with their families and friends explore the complex context for computer use outside school. Having a computer at home does not always equate with being able to use or access it, and peer networks are instrumental in shaping young people’s attitudes towards computers.

Preventing Torture

In December 1998 Lord Woolf, the Master of the Rolls, was guest of honour

at a reception held at the House of Commons to mark the publication of

Preventing torture by Malcolm Evans, Reader in International Law, and

Rod Morgan, Professor of Criminal Justice. This book examines the background

and operation of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture.

It looks at the standards and preventive safeguards which it promulgates

and the response to them by states which are party to the Convention system.

This was underpinned by two years of research, funded by the Airey Neave

Trust, into the practical working of the Convention system and its impact

in member states. The research involved interviews with government officials,

NGOs, lawyers, international organisations and other affected parties

in most European countries.

Preventing torture: a study of the European Convention for the prevention

of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment by R.

E. Morgan and M. D. Evans. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Administrative

Justice in the 21st Century

‘Administrative Justice’ is an elusive concept, but one that goes to the

heart of the relationship between the citizen and the state. It involves:

ensuring that decisions affecting the individual are lawful; that there

are appropriate means for reviewing or appealing decisions where things

have gone wrong; and teasing out the values which should underpin public

administration.

Michael Harris and Martin Partington of the Law Faculty’s Centre for the Study of Administrative Justice, have just pub-lished a major collection of essays which address these issues. In addition Martin Partington has recently chaired a group of academics and practitioners proposing the creation of a Standing Conference on the Resolution of Citizens’ Grievances to review current arrangements.

At a time of great constitutional

change—devolution, the incorporation of the Human Rights Convention, reform

of the House of Lords—it is important that the position of the individual

is not forgotten. The work of the Bristol Centre will play an increasing

part in ensuring that this does not happen.

Administrative justice in the 21st century

edited by M. Harris and M. Partington, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 1999.

Standing Conference on the Resolution of Citizens’ Grievances.

Centre for the Study of Administrative Justice, University of Bristol,

1999.

Aspects of Enlightenment

|

This book by Thomas Osborne, Lecturer in Sociology, won the BSA 1998 Philip Abrams Memorial Prize for the best first sole-authored book. It is not a treatise on the 18th-century movement of the Enlightenment, rather it studies enlightenment in a more general sense, as an ethos, rather than as a dogma to be analysed or defended. |

The author sees enlightenment as concerned

with the pursuit of knowledge; it has ‘an aspiration, an ideal, a spirit’.

The central chapters of the book consider the critical aspects and implications

of scientific, therapeutic and aesthetic kinds of enlightenment. Thomas

Osborne aims ‘not to attempt a theoretical excavation of the topic but

to describe it when in use; to treat of enlightenment not like an engine

idling but when it is doing work.’ Hence he envisages a more modest form

of social theory, one which does not aim to characterise whole societies.

This theory is essentially parasitic, focusing on the ways in which knowledge

is pursued in a variety of arenas, rather than claiming any of these arenas

as its own sphere of expertise.

Aspects of Enlightenment: social theory and the ethics of truth

by Thomas Osborne, UCL Press (Taylor & Francis Group), 1998.

Reference

Guide to Russian Literature

This imposing volume received two accolades

in 1998: it was named in the Outstanding References List of the American

Library Association and in the Outstanding Academic Books list of Choice.

In over 1,000 pages it includes entries on some 273 writers and 293 works.

The Guide covers the entirety of Russian literature although ‘there is

an unashamed bias towards the 19th and 20th centuries.’ Neil Cornwell,

the editor, is Professor of Russian and Comparative Literature. He has

imposed strict editorial guidelines on the 180 contributors who come from

Europe, Russia and Australasia, as well as North America and the British

Isles and include emeritus professors and a wide range of leading active

academic Slavists, as well as junior lecturers, independent scholars and

graduate students.

|

Illustration by Bilibin to Pushkin's The Tale of Tsar Saltan |

The entry on each author is of standard length and format. This has the interesting effect of giving more detail than is usual on the lesser-known writers. However, for the more important writers there are essays on their principal works. These may have come from a variety of contributors and therefore illuminate the subject from different angles.

Drawing together important themes

and periods of Russian literature are a series of 13 introductory essays.

All these are written by specialists covering such fields as Tre-Revolutionary

Russian theatre, 18th-century Russian literature, Pushkin, women’s writing

in Russia, and Russian literature in the post-Soviet period. This scholarly

work is preceded by useful alphabetical and chronological lists of the

writers, a general reading list and a chronology of Russian literary history.

Neil Cornwell, and the associate editor, Nicole Christian, also from Bristol,

have produced an impressive work which is an excellent tool for students

and will doubtless become a standard reference work for specialists too.

Reference guide to Russian literature edited by Neil Cornwell,

Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1998.

The Collier Chair

Making science accessible to the public has long been one of the University’s

aims. This year has seen the appointment of the first three holders of

the University’s Collier Chair in the Public Understanding of Science

and Technology. Professor Peter Cochrane, OBE, FREng, Head of BT Laboratories

Advanced Research, Dr Sally Duensing, Assistant Director, Science and

Museum Liaison, the Exploratorium, San Francisco, and Sir Neil Cossons,

OBE, Director of the Science Museum, will each hold the appointment for

a year. The title of the Chair commemorates the late Dr John Collier,

FRS, FREng, former Chairman of Nuclear Electric and a Patron of the Campaign

for Resource, and honours his work in communicating the benefits of science

and technology as a force for good in the community. The Chair is funded

by a consortium of nearly 30 corporate donors and charitable trusts, headed

by Nuclear Electric. Sponsors include BNFL, SmithKline Beecham, Strachan

& Henshaw, a group of Japanese companies and the Garfield Weston Foundation.

The Collier Professors are members of the University’s Institute for Advanced Studies in which eminent scholars from many parts of the world spend a period working in Bristol in order to seed research collaboration.