Articles & Reviews

Vera Drake

Now I am not being naïve; I have been a frequent patron of the Watershed for a long time and am familiar with its clientele. Yet as I stood in line with dozens of chattering couples and well-preserved ladies, silently berating myself for not bringing a friend, I couldn’t help but be a little confused or, more precisely, curious: do these people know what Mike Leigh is about? Do they even know who he is? His films have been described as bleak, gritty, and melancholic. His working methods are characterised by low-budgets and extensive improvisation. That these well-fed, well-tanned people were queuing early for a film by the socially-aware, independent film-maker Leigh amused me. I felt as if I had wandered into a British remake of the American film Pecker, in which af.uent city-types patronisingly consume photos of the working-class. Fortunately, however, this was not to be a remake, not even a typically shoddy one.

Leigh’s films are consistently accused of being depressing, his modus operandi experimental. This may be true, but his social satire is moderated by his sensitivity, his unorthodox methods by an ability to extract the best from his actors (see the amazing .fteen-minute improvised café scene in Secrets And Lies). This is what makes his films accessible, and liable to attract both art-house veterans and the middle-brow Watershed regulars alike. As such, there was never any doubt that Vera Drake would be a success, both here and on the international scene, where the picture received the coveted Golden Lion at Venice and Imelda Staunton the accolade of best actress.

Staunton’s performance has been much praised already, and it is well deserved. Her portrayal of the eponymous mother-hen figure who runs a secret back-street abortion service is truly outstanding, working much nuance and subtlety into an understated character. The supporting cast is equally impressive, with, amongst others, Alex Kelly and Phil Davis providing the familial setup. And the familial setup is very important. As in many of his other films (especially Secrets And Lies), the emphasis is on domestic, localised dramas; no guns, no conspiracy theories. Even though it deals with the timeless and universal issue of abortion, Leigh resists philosophical musings and abstract, moral illustrations. What we see is not a critique of the law-passing administration, but a microcosm, a wall-papered living-room of a stage. For a film with such a topical issue at its core, it may seem surprising that the word ‘abortion’ is rarely mentioned in the film (in fact, I don’t even recall a single utterance).

This idea of the unsaid is integral to the film; ‘I help young girls out’ is the evasive defence relied upon by Vera when confronted with her criminal acts. Along with her mantra-like ‘Cuppa tea, luv?’, it is the routine, the familiar that protects her secret life. With these two phrases she justifies her double-existence, adhering to the belief that problems sufficiently painted with euphemisms disappear. Unsurprisingly, this is shown to be false, as her criminal acts are exposed and she is sent to prison. And that, dear reader, is the plot. Simple enough. But a simple plot doesn’t necessitate a simple film.

One of the most telling scenes in the film is the one in which Vera reveals her secret to her husband. The two sit facing each other in a police interview room. Vera is too shocked to speak, but slowly and with great difficulty engages her lip and tongue muscles, draws closer and closer to her husband. Finally, she stirs up enough courage to tell him, but only through a whisper into his ear (inaudible to us), and even then, one could almost suspect her words to be ‘I help young girls’. Leigh doesn’t arbitrarily dramatise for the sake of drama, and neither do his characters.

The film is set in early 1950s London. Logistics-wise this was an obvious choice; the revised law on abortion was introduced in 1957. However, the final entry of the film’s closing credits reveals something more – Leigh dedicates the film to his parents, a midwife and a doctor (the 50s being a time in which they both would have practiced), so perhaps this is one of Leigh’s more personal offerings. Indeed, it might also be remembered that the subject of unwanted pregnancies is a recurrent theme in his work. In Secrets And Lies, an adopted woman searches for her biological mother, for whom she is a secret kept from her other daughter. But to infer too much from these observations would be to do Leigh an injustice, and an ironic injustice at that, given the great complexity of his fictional characters. Despite his efforts, however, accusations of stereotyping have been levelled against much of his work, and some characters in Vera Drake (such as Vera’s ‘mockney’ son Sid) do indeed veer dangerously close to justifying this. The sad truth is that, due to Leigh’s aversion to extreme characterisation, objections of this type can emerge from what is often quite simply the portrayal of a character’s mundane and banal nature. Leigh’s interest lies in the everyman and the everyday, not the extraordinary.

No doubt this is why he chose the small black box as his medium for the greater part of the seventies and eighties. Television films such as the claustrophobically observational Abigail’s Party and the oft-quoted Nuts In May are just as important within his body of work as his later bigscreen efforts. And Vera Drake is a fine effort, a much needed reminder that British film-making is still alive (it was made by an entirely homegrown cast and crew). However, Leigh’s cause is not one to be celebrated solely by his countrymen. His successful yet unorthodox techniques serve as living proof that today’s film-makers can avoid the temptations of Hollywood, survive on a shoe-string budget and still attract much of the mainstream. It ought to be considered fortunate that Leigh, with his lowbudgets and no-nonsense approach, hasn’t been and won’t be affected by the recent retraction of tax-cuts for British film productions; one senses he still has many more films in him (now sixty-one, he has yet to show any desire to retire). Which is all the better for us, seeing as how otherwise our independent cinemas would be occupied solely by pretentious, rambling film-students.

Dir: Mike Leigh

Running Time: 125 mins

UK (2004)

Alan Tang

Reconstruction and Fabrication

Art should be about challenging preconceptions. In 1968, Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge and David Rushton arrived at the conclusion that the Art Establishment had lost sight of this ideal, it having retreated into a world of fixed and restrictive conventions. Their protest led to the formation of the controversial Art and Language Group, which harnessed the power of the written word and used text as a key tool in articulating their message. This long-awaited exhibition documents the strange yet enlightening results of their rebellion.

The group believed the modernist movement in particular was inadequate as its focus was primarily on appearance, displaying work with little or no guidance as to meaning. At the same time literary debate was questioning the autonomy of the author and promoting the role of the reader in the interpretation of the text. Art-Language contests the idea that the viewer of art is free to interpret as they please. As with literature, there should be collaboration between the original ideas of the artist and the subsequent interpretation of the spectator. Bainbridge’s M1 (Machine One) has no fixed visual form, it requires a viewer in order to become a piece of art. Each encounter will be different, demonstrating not only the importance of participation but also the limitations of an artist’s in.uence once the work has left his hands.

Atkinson’s ‘Triptych: Meme and Homo Heidebergenis’ emphasises the role of the artist in the viewing process. The spectator follows a visual path across the three monotone grey canvases, the focal point of which is a screen of scrolling text - a crude representation of the flow of ideas from the artist’s mind to our own. The final canvas is left blank, inviting us to project our thoughts. The result is to make us acutely aware of the extent to which we owe our understanding of the piece to Atkinson himself.

Textual accompaniment to the visual is of key importance to Art-Language as it allows the artist to minimise subsequent misinterpretation of his work. In the video interview on display at the exhibition, Bainbridge acknowledges the paradox between the beauty of his industrial paintings and the bleakness of the story behind them. The understanding achieved by the written explanation is conveyed well in Rushton’s ‘Pripyat: Early One Morning’. As the viewer peeps through the slot to view a tiny model of a decaying nursery classroom, they are confronted with the sinister image of a painting of Lenin, triumphantly unscathed amongst the peeling and dripping walls. The accompanying text adds depth to the haunting composition by revealing that the original room was found in Chernobyl, provoking further thought and questions.

Far from being repressive, the text that is central to Art-Language empowers the viewer, enabling them to challenge their own preconceptions about art. This is in many ways a disorientating exhibition – but one leaves feeling that this is precisely the effect that Art-Language are aiming to achieve.

Reconstruction and Fabrication ran at the ICIA Gallery in Bath from 19th November to 16th December 2004.

Amy Gardner

The Bacchae

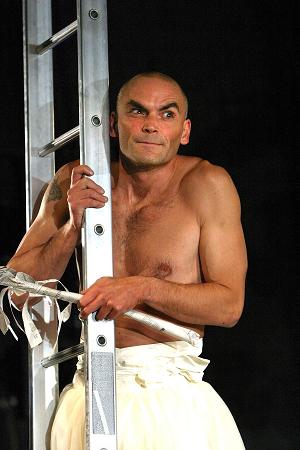

Cornwall-based company Kneehigh Theatre have taken Euripides’ classical tragedy and brought it into the twenty-first century with dazzling effect. The play tells the story of Dionysus, god of wine, who returns to Thebes to confront his mortal family. They have denied him his status as a deity, and despite much evidence to the contrary, King Pentheus repeatedly refuses to accept Dionysus as a god. Dionysus then proceeds to exact his revenge, culminating in the bloody death of Pentheus at the hands of his own mother, Agave. She, along with many of the women of Thebes, has been seduced by the cult of Dionysus, which encourages drunken abandon on the mountainsides surrounding Thebes. Although Kneehigh Theatre’s production of the play has been extensively rewritten into modern English, it remains remarkably true to the original plot. Dionysus himself is fabulously camped-up in gold stilettos, as an initially seductive human character who, as the play progresses, shifts into a merciless and vengeful god. The production is fast paced and frenetic, the traditional Greek chorus - here reworked as hilariously mischevious cross-dressing men - moving the action along with song, dance and audience participation. The choreography is excellent throughout; and the audience were carried away by this energetic and extremely engaging production. The mood of the play is at first carefree and seductive, but as the plot develops it becomes dramatically sinister as the true extent of Dionysus’s power is revealed.

Yet why is there still such appeal in producing a play that is thousands of years old? Classical drama is continuously being reinvented and modernised; indeed, the Bristol Old Vic is also staging Odysseus in its current run. For me, the key to this enduring appeal lies in the universality of the themes encompassed in these ancient works. The Bacchae is preoccupied with revenge, betrayal, pride, obsession and intrigue, topics which remain seductive to a modern audience. They comprehensively relate to fundamental and enduring human experiences. In Dionysus himself, parallels can be made with the cult that surrounds modern celebrity and the effect that they can have on normal people. Here the glamour surrounding such figures is expressed, initially appearing as a benign force until its true brutality is revealed. Dionysus inspires a fanatical following of devoted worshippers, whose obsession develops its own momentum until, blinded to reality, they murder their king. Nearly three thousand years on, religion is still capable of spawning the same fanaticism; this is an issue that is still pressingly important to today’s society.

In their moving version of The Bacchae, Kneehigh Theatre have succeeded in creating a production that enlivens and makes relevant an ancient drama in an extremely modern way. Their energy and passion will leave you lost for words; this is clearly a cast with great enthusiasm for its performance. Highly recommended.

The Bacchae runs at the Bristol Old Vic January 25th - February 12th.

Catherine Davies